A Brief History of Skating and Ice-Rinks

The first presumptive evidence of skating is from about 3000 years ago, a crude ice skate made from bone having been discovered in Switzerland, dating to around 1800 BC. Gliding on ice afforded both a quicker and less energetic mode of transport compared with travelling on foot. Both these factors would obviously be of huge value to hunter-gatherers in particular, who would have been able in this way to increase their area of foraging (the latter increases by the square of the linear distance travelled) and thus gain advantage over their non-skating neighbours. It has been suggested that ice skating remained the most efficient method of human-powered travel until the bicycle was invented in the first half of the 19th century.

The first written record of ice skating is in about 1190 by William Fitzstephen, who described children playing on frozen rivers in London. These skaters propelled themselves across the ice with sticks, like skiers do on snow. Skates with blades were introduced in the 13th or 14th century, probably in Holland or Scandinavia, enabling skaters to proceed faster and without sticks. The Patron Saint of skating is St Litwinia, a Dutch lady whose fall on the ice was immortalized in a 15th century woodcut.

Modern ice skating dates from 1742 with the founding of the Edinburgh Skating Club. London followed in 1830 with The Skating Club. It became a popular pastime, especially among the aristocracy: Prince Albert is recorded as falling through the ice while skating on a lake in Buckingham Palace in 1841. Most skating took place on natural ice, such as frozen rivers or the East Anglian Fens, but deliberate attempts were also made to create good conditions for the sport, for instance in Regent's Park, where a shallow area was flooded and allowed to freeze. This was an early example of what we know now as an “ice rink”. The word “rink” seems to be derived from a Scottish term originally used to described a pitch for the sport of curling or quoits [footnote 1]. The word occurs, in the context of a frozen field, in one of Burns' poems in 1787.

An important step forward was made in 1843, when an establishment called a Glaciarium was opened in the Baker Street Bazaar. This was an indoor stretch of a skating surface (not ice) produced artificially by a mixture of chemicals, the invention of Henry Kirk. It was described in an advertisement in the Illustrated London News as “.. enlivened with chaste music, is indeed a delightful cool resort, and the admittance of one shilling, very moderate”. The same journal reported on 1 April 1843 that Prince Albert had visited the Glaciarium, skated and declared his intention of going again. The Grand Duke Michael of Russia visited on October 30. In The Times the public was informed that it was “..Open from 9 o'clock in the morning till 11 exclusively for lady scaters (sic) with female attendants..” Despite the royal endorsements, the enterprise was not a success, as the surface was mushy and the atmosphere smelly, and it did not last for long.

A technically more successful Glaciarium, with a skating surface of real ice, was opened in 1876, at 379 Kings Road, London, using the freezing method invented by John Gamgee, that consisted of copper pipes below the ice layer, through which was circulated a mixture of chemicals (details are given in The Times 2 May 1876- see footnote 2). Gamgee was a veterinary surgeon turned inventor and engineer who also became an expert at freezing meat on a commercial scale. He opened two more such arenas, a “floating glaciarium” on the Thames at Charing Cross and a rink in Manchester; however, all these were short-lived. The Southport Glaciarium, using Gamgee's method, was opened in 1879, and fared little better, being forced to close after only 10 years. Other countries were not far behind – the first indoor rink in the USA was opened in 1879 (Madison Square Gardens) and in Canada in 1912 (Victoria, British Columbia).

Ice lends itself to many leisure pursuits: besides straightforward skating, there are for example codified forms of figure skating, ice dancing and speed skating; skating became an Olympic sport in 1908. There are also games, such as ice hockey (extremely popular in USA and Canada) and curling; these attained Olympic status in 1920 and 1998, respectively. Bandy is a game superficially similar to ice hockey, but using a ball rather than a puck; it was an Olympic demonstration sport in 1952, but has not attained full status. As a result of these several attractions, there are now a large number of ice rinks found around the world (for example, more than 1700 in USA). A recent innovation is the pop-up ice-rink, that is now very popular around Christmas.

Ft 1: In curling, “rink” is now used to describe the team, rather than the pitch

Ft 2: Gamgee exploited the recently-discovered phenomenon known as the Joule-Thomson effect. When a compressed gas is allowed to expand, marked cooling occurs. This can be observed eg when using as fire extinguisher or filling a gas lighter. The reverse phenomenon, ie heating when a gas is compressed, is seen when pumping up bicycle tyres. Local History It is stated in the account by The Museum of Twickenham, and in Wikipedia, Richmond Borough's The Building of a Borough,and by Richard Meacock (www.icerinx.com) that the ice rink was built on land given to Twickenham UDC by George, Duke of Cambridge for “leisure purposes”. The latter statement presents a bit of a puzzle.

The Duke did indeed have close connections with the neighbourhood – he was Ranger of Richmond Park and the owner of Kew Cottage – but it appears that he did not own the land (and never had owned it) on which the rink was built. The rink was located on Clevedon Road, that had been newly formed in the first few years of the 20th century (first appearing Kelly's Directory in 1908; Cambridge Road was originally known as Clevedon Road) on part of the former estate of Cambridge House . The latter had no connection whatever with the eponymous Duke, deriving its name from the distinguished 18th century poet and essayist Richard Owen Cambridge, who lived there for 50 years. Its history, occupants and owners have been well described by Maureen Bunch (BoTLHS #63 and 68). The land surrounding the House, originally copyhold to the Manor of Isleworth, had been given to the Earl of Northumberland by James I in 1604; the estate remained intact until 1897, when the executors of Sir Edward Paul (the most recent occupier and owner, who died 1895) sold it to a property developer named Henry Foulkes. The Rate Books for Twickenham dated 29 October 1910 show that Foulkes owned not only Cambridge House (then occupied by The Middlesex Country Club), but also an adjoining property occupied by “Twickenham Olympia”, and land in the name of “Skating Rink Ltd”.

The latter refers to an enterprise, Richmond and Twickenham Skating Rink Co Ltd, launched by a business man Charles Bedworth (and others), the purpose of which was to build a roller skating rink. An advertisement in The Richmond and Twickenham Times on June 12 1909 encouraged investors to buy shares, with the inducement that Mr Bedworth “believes that the shareholders will receive dividends much in excess of their capital invested within the first year..”. It is noted that Mr Bedworth was managing director and/or chairman of four other such rinks, in Harrogate, Oldham, Bolton and Leamington. Unfortunately, Mr Bedworth's optimism and business acumen were ill-founded, as by 1912 all these rinks had closed and the companies owning them had gone into liquidation. Work had started on constructing the Twickenham site (the advertisement had stressed that the building would be made of brick, and thus be permanent and a valuable asset) between Clevedon Road and Cambridge Road, one minute's walk from the terminus of London United Tramways Ltd. However, the failure of the Company meant that the building was unfinished, and remained so until 1914.

The building that subsequently housed the skating rink thus had an inauspicious start. It was originally intended for roller skating, but the company involved went into liquidation in 1912 before the rink had opened. Investors’ money was lost, but the shell of a brick building had been constructed, and stood empty.

Shortly after the start of World War 1, the Belgian entrepreneur Charles Pelabon set up his munitions factory on the site. This remained in production until the end of the war in 1918.

Other buildings were erected on the site during the war, all stipulated by the Council to be removed when peace arrives. However, it is clear that this not happen. In 1920 M Pelabon asked not to be held to the original agreements to sell the land back within 5 years of hostilities having ceased, and he was given permission to change his type of production.

Eventually the Council, having made several concessions to M Pelabon, started to press him to fulfil his obligations. Also, the East Twickenham Ratepayers Association became concerned over the continued use of this land for heavy industry. In February 1925 the Association formally complained to the UDC about the lack of action against M Pelabon. In reply, the UDC stated was that it had earlier been “helpless to prevent it”, for two reasons; first, the various restrictive agreements that had been made with M Pelabon, second that he had returned to the Continent and could not be contacted. Shortly afterwards, M Pelabon was asked to contribute £1,500 towards the construction of a pleasure ground (this had originally been suggested in 1919); he agreed to pay £1,250.

According to Kelly’s Directory for 1925, the Pelabon works had disappeared from the site, that was now occupied by other factories. At the end of 1925 the Council bought back ther land for £4000. A counter offer from a manufacturer wishing to make “confectionery” was turned down.

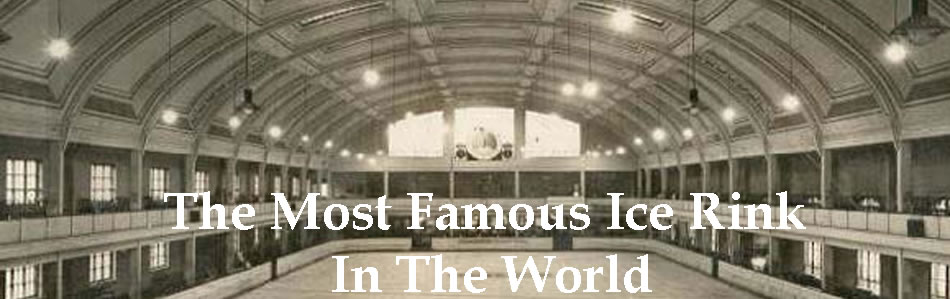

In May 1928 a proposal made to adapt the former Pelabon Works as an ice skating rink, under the management of the Richmond Ice Skating Rink Co., was agreed, and in December 1928 the ice rink was opened. This was a spectacular affair, according to Richmond & Twickenham Times Dec 22: the ribbon was cut by Lady Hoare, wife of the Air Minister, in the presence of many local dignitaries and international skaters. Eight hundred skaters took to the ice “without the least suggestion of crowding”. There was initial success: between 1 Jan and 15 May 1929 there were more than 120,000 visitors to the rink, and a profit of more than £9000 was reported. However, despite early enthusiasm, it is evident that this venture was not an unqualified success. The rink was operated as a club (involving membership), rather than a place of entertainment for the general public. The rink closed in 31 May 1931, at the end of its normal “season” (October – May), following Fancy Dress on Ice and a New Year Carnival, but when it reopened on 2 October, with a Civic ceremony, it was under entirely new management, and alterations had been made. It was also in future to be called “Richmond and Twickenham Ice Rink” - later to become The Sportsdrome.

I am most grateful to Elaine Hooper, Archivist at The National Ice Skating Association of Great Britain and NI, for very helpful comments,

Jeremy Hamilton-Miller

Chairman, Richmond Environmental Information Centre

Link to a snapshop from Richard Meacock's original website HERE